Professional illustration about Acorns

What Are Acorns?

What Are Acorns?

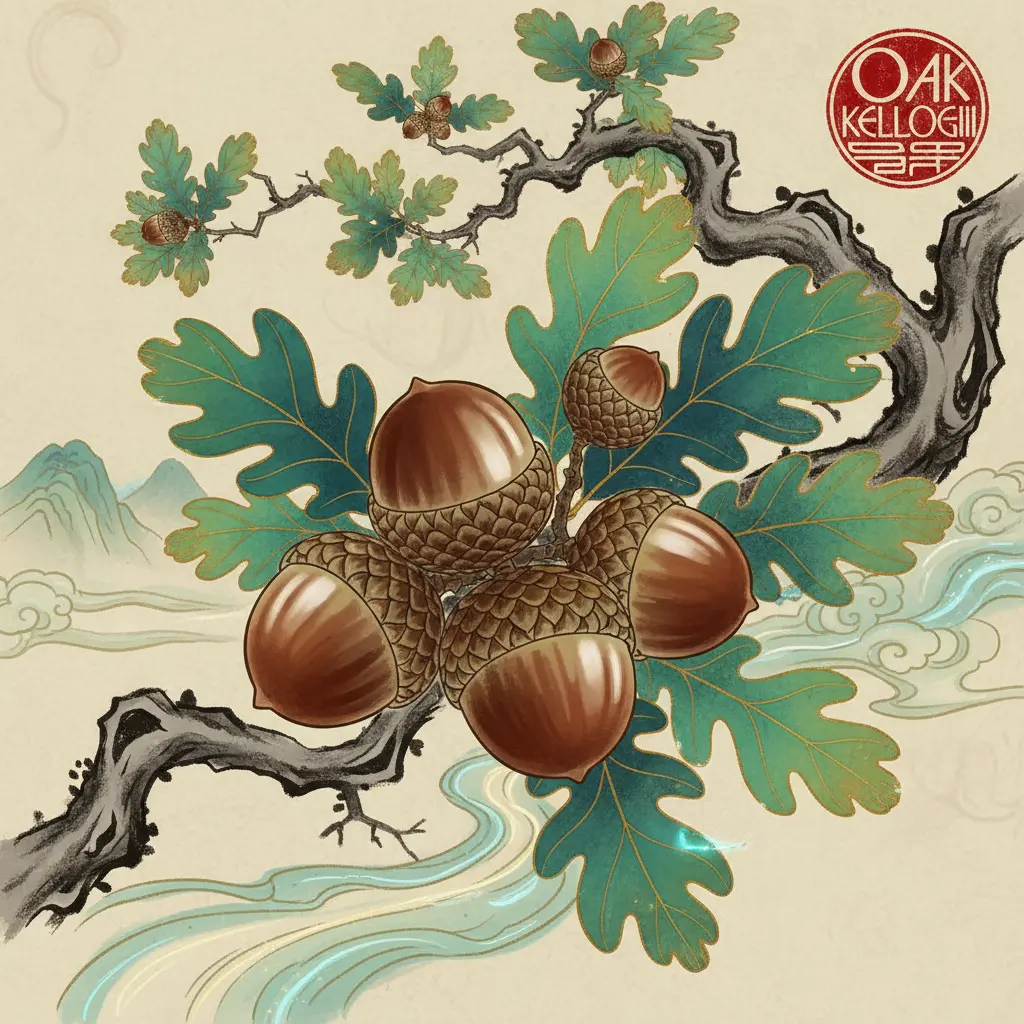

Acorns are the nut-like seeds produced by oak trees (Quercus spp.), a cornerstone species in forest ecosystems worldwide. These small, oval-shaped nuts are encased in a tough outer shell called a cupule, often resembling tiny helmets. Found in varieties like the English oak, white oak, and scarlet oak, acorns play a vital role in wildlife diets, forest regeneration, and even human traditions. Rich in fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, they’re a high-energy food source for deer, squirrels, and rodents, especially during autumn when they drop in abundance—a phenomenon known as mast.

But acorns aren’t just wildlife snacks. Historically, humans have used them as a survival food, grinding them into acorn flour after leaching out bitter tannins. Native American tribes and Korean cuisine, for example, have long incorporated processed acorns into breads and porridges. The preparation involves soaking or boiling to remove tannins, which can be toxic in large quantities. Modern foragers still practice these methods, highlighting acorns’ nutritional value as a gluten-free, mineral-rich alternative to grains.

Ecologically, acorns are powerhouse seeds. Their dispersal—often by animals caching them—fuels seedling development and sustains biodiversity. Oaks like the Southern red oak and Quercus kelloggii (California black oak) rely on this symbiosis; squirrels bury acorns, some of which sprout into new trees. Meanwhile, the Fagaceae family’s evolutionary adaptations ensure acorns survive harsh conditions, from drought to predation.

Beyond practicality, acorns carry symbolism—representing strength, potential, and resilience in cultures from Celtic lore to modern branding (think “mighty oaks from little acorns grow”). Whether you’re a gardener battling squirrel raids, a chef experimenting with roasted acorns, or a nature lover marveling at forest ecology, these humble nuts are a microcosm of life’s interconnectedness. Just remember: not all acorns are created equal. Some, like those from willow oaks, have lower tannin levels, making them sweeter and easier to process—a handy tip for foragers!

Fun fact: A single oak tree can produce over 10,000 acorns in a mast year, creating a ripple effect across entire ecosystems.

Professional illustration about English

Acorns Investing Basics

Acorns Investing Basics: From Forest Ecology to Practical Uses

When we talk about acorns, we're diving into the world of Fagaceae, the oak family that includes species like English oak (Quercus robur), white oak (Quercus alba), and Southern red oak (Quercus falcata). These tiny nuts are more than just wildlife food—they’re packed with nutritional value, rich in fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, making them a powerhouse for both animals and humans. But before you start foraging, it’s crucial to understand the basics of acorn preparation, especially since some varieties contain high levels of tannins, which can be toxic if not properly leached.

Why Acorns Matter in Forest Ecology

Acorns play a vital role in forest ecology as a key component of mast, the cyclical production of nuts and seeds that sustains wildlife. Species like deer, squirrels, and rodents rely heavily on acorns for survival, especially in winter when other food sources are scarce. This relationship also aids in seed dispersal, as animals bury or transport acorns, promoting seedling development and oak forest regeneration. Interestingly, not all acorns are created equal—Quercus kelloggii (California black oak) produces sweeter nuts favored by wildlife, while scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea) acorns are more bitter due to higher tannin content.

From Foraging to Food: How to Process Acorns

Cultural and Practical Significance

Beyond ecology and cuisine, acorns hold deep symbolism in many cultures, representing strength, potential, and resilience. Indigenous communities have long used acorns as a traditional food, grinding them into meal for breads and porridges. Today, with growing interest in wild edibles, acorns are gaining attention as a sustainable, nutrient-dense resource. However, always research local oak species—willow oak (Quercus phellos) acorns, for example, are smaller and may require extra processing effort.

Wildlife and Human Connections

The interplay between acorns and wildlife diet is fascinating. Squirrels, for instance, practice "scatter hoarding," burying acorns to eat later, which inadvertently plants new trees. For humans, acorns offer a biological dispersal lesson in patience and preparation. Whether you’re a forager, a gardener, or simply curious about forest mast cycles, understanding acorns opens a window into nature’s intricate systems. Just remember: proper identification and processing are key to unlocking their potential—safely and deliciously.

Professional illustration about Quercus

Acorns vs Competitors

When comparing acorns to other nuts and seeds in terms of ecological roles, nutritional value, and human uses, it’s clear they hold a unique position—especially within the Fagaceae family. Unlike commercial nuts like almonds or walnuts, acorns are wild-harvested and deeply tied to forest ecology, serving as a critical mast resource for wildlife. For example, deer, squirrels, and rodents rely heavily on acorns for winter survival, while many cultivated nuts are primarily grown for human consumption. This distinction makes acorns a keystone species in ecosystems where English oak, white oak, or Quercus kelloggii dominate.

Nutritionally, acorns stand out for their versatility but require more preparation than competitors. While almonds and cashews are ready to eat after minimal processing, acorns contain tannins, which must be leached to remove bitterness. However, once prepared, acorn flour rivals grain flours in protein and healthy fats, offering a gluten-free alternative with a rich, nutty flavor. Traditional cultures, particularly Native American communities, have long valued acorns as a traditional food, roasting them or grinding them into meal. Modern foragers are rediscovering these techniques, with roasted acorns gaining popularity as a sustainable, low-cost superfood.

From a biological dispersal perspective, acorns have a competitive edge over smaller seeds like sunflower or pumpkin seeds. Their size and weight allow them to establish robust seedling development, often aided by animals like squirrels that bury them (a form of seed dispersal). In contrast, many commercial nuts rely on human planting and agricultural systems. This natural regeneration makes oaks like scarlet oak and southern red oak vital for reforestation projects.

Yet, acorns face challenges that cultivated nuts don’t. Their tannin leaching process is time-consuming, and inconsistent harvests due to weather fluctuations can limit availability. Meanwhile, walnuts and pecans benefit from standardized farming practices. For foragers, understanding acorn storage methods—like drying or freezing—is crucial to preserve their nutritional value.

Symbolically, acorns also carry weight that mass-produced nuts lack. In folklore, they represent potential and resilience (think "mighty oaks from little acorns grow"), whereas almonds or hazelnuts lack this acorn symbolism. Whether you’re a wildlife enthusiast, a survivalist, or a chef experimenting with oak nut recipes, acorns offer a connection to nature that their competitors simply can’t match.

For those exploring acorns as a food source, here’s a quick comparison to common nuts:

- Protein content: Acorns (8g per 100g) vs. Almonds (21g per 100g) — lower but still significant, especially when paired with other protein sources.

- Fat profile: Acorns are higher in monounsaturated fats (similar to olive oil) compared to walnuts, which are richer in polyunsaturated fats.

- Toxicity: Raw acorns contain acorn toxicity due to tannins, whereas cashews are toxic only if improperly processed (their shells contain urushiol).

- Wildlife impact: Acorns support entire ecosystems, while farmed nuts often require pesticides that harm pollinators.

In summary, while acorns may not compete with almonds or pecans in convenience, their ecological importance, cultural heritage, and nutritional potential make them a standout choice for those willing to put in the effort. Whether you’re leaching tannins for acorn preparation or observing Quercus species in the wild, acorns offer a depth of interaction that commercial nuts rarely provide.

Professional illustration about kelloggii

Acorns Fees Explained

Understanding Acorns Fees: What You Need to Know in 2025

When discussing acorns, most people think of the iconic oak nut dropped by trees like the English oak (Quercus robur), white oak (Quercus alba), or scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea). But beyond their role in forest ecology and as a food source for deer, squirrels, and rodents, acorns have practical uses for humans—if you know how to process them properly. One of the biggest hurdles? Dealing with tannins, naturally occurring compounds that make raw acorns bitter and potentially toxic. Here’s a breakdown of the "fees" (or costs) associated with harvesting and preparing acorns, whether for acorn flour, roasted acorns, or other traditional foods.

The Time Investment: Harvesting and Preparation

The first "fee" is time. Collecting acorns isn’t as simple as scooping them off the ground. You’ll need to sort through them, discarding any with holes (a sign of insect infestation) or mold. Species like the Southern red oak (Quercus falcata) or willow oak (Quercus phellos) produce acorns with varying tannin levels, so identifying your local Quercus species is crucial. Once harvested, the real work begins: tannin leaching. This process involves soaking or boiling acorns to remove bitterness, which can take hours or even days depending on the method. Cold leaching (soaking in water) is slower but preserves more nutrients, while hot leaching (boiling) is faster but may reduce nutritional value.

Equipment and Storage Costs

If you’re serious about turning acorns into food, you’ll need basic tools: a nutcracker or hammer for shelling, a blender or mortar and pestle for grinding, and containers for acorn storage. While these aren’t expensive, they add up if you’re starting from scratch. Storing acorns long-term requires drying them thoroughly to prevent spoilage—another time-sensitive step. For those interested in acorn flour, a grain mill or high-powered blender is essential for achieving a fine consistency.

The Hidden "Fee": Learning Curve

Unlike store-bought nuts, acorns demand knowledge to avoid acorn toxicity. For example, Quercus kelloggii (California black oak) acorns have lower tannins than others, making them easier to process, while some Fagaceae family members require extensive leaching. Mistakes can lead to wasted effort or even stomach upset, so researching your local oak species is a non-negotiable step. Communities with a history of using traditional food sources often have the best tips—like roasting acorns before leaching to enhance flavor.

Wildlife Competition and Ecological Impact

Another indirect "fee" is competing with wildlife. Acorns are a critical part of the wildlife diet, especially during mast years (when oaks produce abundant nuts). Overharvesting can disrupt seed dispersal and seedling development, affecting forest ecology. Ethical foragers recommend taking only what they need and leaving plenty for biological dispersal by animals. In some areas, regulations may limit harvesting, so always check local guidelines.

Is It Worth the Effort?

Foraging acorns isn’t for everyone, but the rewards can be significant. Acorn flour is gluten-free, rich in healthy fats, and a sustainable alternative to commercial flours. Roasted acorns make a nutritious snack, and their symbolism in cultures worldwide adds a layer of connection to nature. If you’re willing to pay the "fees" of time, effort, and learning, acorns offer a unique way to engage with forest ecology while creating wholesome food. Just remember: patience and respect for the process (and the ecosystem) are key.

Professional illustration about White

Acorns Round-Ups Guide

Acorns Round-Ups Guide: Harvesting, Processing, and Storing Nature’s Nutrient-Packed Nuts

Foraging for acorns—whether from the English oak (Quercus robur), white oak (Quercus alba), or Southern red oak (Quercus falcata)—is a rewarding way to connect with forest ecology while securing a versatile wild food source. But before you start scooping up these oak nuts, it’s crucial to know how to round them up efficiently and sustainably. Here’s a detailed guide to acorn harvesting, from identifying prime trees to post-collection processing.

1. Timing Your Harvest

Acorns mature in late summer to early fall, but the exact timing depends on the species. For example, Quercus kelloggii (California black oak) drops its acorns earlier than willow oak (Quercus phellos). Watch for signs like caps loosening or a slight color change. Pro tip: Visit oak groves after a windy day—nature’s way of doing the round-up for you! Avoid collecting too early; immature acorns are often higher in tannins, which cause bitterness and require extra processing.

2. Selecting the Best Acorns

Not all acorns are created equal. Prioritize:

- Plump, uncracked nuts: These are fresher and less likely to harbor mold or pests.

- Brown, glossy shells: Green or shriveled acorns may be underripe or rotten.

- Intact caps: While caps often detach during falling, those still attached can indicate recent drops.

3. Efficient Collection Methods

- Hand-picking: Ideal for small batches. Wear gloves to avoid tannin stains.

- Raking or sweeping: Use a wide-toothed rake to gather acorns from leaf litter without damaging them.

- Tarp method: Spread a tarp under the tree and shake branches gently (works best with scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea), which has brittle twigs).

4. Sorting and Cleaning

After your round-up, sort acorns by floating them in water. Discard any that float—they’re likely hollow or infested by rodents or insects. Rinse the keepers in cold water to remove dirt and debris. For long-term acorn storage, dry them in a single layer on screens or trays in a well-ventilated area for 2–3 weeks.

5. Processing for Edibility

Raw acorns contain tannins, which are bitter and can be toxic in large quantities. Here’s how to leach them:

- Cold leaching: Soak shelled, crushed acorns in cold water for several days, changing the water daily until it runs clear. Best for acorn flour.

- Hot leaching: Boil acorns in multiple changes of water until the bitterness fades. Faster but may reduce nutritional value.

6. Creative Uses for Harvested Acorns

- Roasted acorns: Toss shelled acorns with salt and roast at 350°F for 15–20 minutes for a crunchy snack.

- Acorn flour: Grind leached acorns into flour for gluten-free baking (popular in traditional food prep).

- Wildlife support: Leave a portion of your harvest for deer, squirrels, and other animals that rely on mast for winter survival.

7. Storing Your Bounty

Proper storage prevents spoilage and preserves nutritional value:

- Short-term: Keep dried, unshelled acorns in breathable bags in a cool, dark place (up to 6 months).

- Long-term: Freeze shelled acorns or vacuum-seal them to prevent rancidity.

Bonus: Ethical Foraging Tips

- Only take what you’ll use, leaving plenty for seed dispersal and seedling development.

- Avoid overharvesting from a single tree to support forest ecology.

- Respect local regulations—some parks prohibit foraging.

By mastering the acorns round-up process, you’ll unlock a free, nutritious resource while contributing to the balance of your local ecosystem. Whether you’re baking with acorn flour or observing wildlife diet habits, these nuts offer endless opportunities for learning and sustainability.

Professional illustration about Willow

Acorns Found Money

Acorns Found Money: How These Tiny Nuts Offer Big Value in 2025

For centuries, acorns—the nuts produced by oaks like Quercus robur (English oak), Quercus kelloggii (California black oak), and Quercus alba (white oak)—have been a hidden treasure in forest ecology. But in 2025, they’re gaining renewed attention as a sustainable, versatile resource with surprising economic and ecological benefits. Whether you’re foraging, investing in forest mast crops, or supporting wildlife habitats, acorns are proving to be "found money" in more ways than one.

From Foraging to Food Innovation

Wildlife and Forest Ecology’s Hidden Currency

In forest ecosystems, acorns are a cornerstone of mast cycles, feeding everything from rodents to birds. Species like the willow oak produce smaller, sweeter acorns favored by squirrels, which play a critical role in seed dispersal. Deer rely heavily on white oak acorns in fall, making them a hotspot for wildlife photographers and hunters alike. This biological dispersal system ensures oak regeneration—meaning healthy acorn crops directly translate to thriving forests.

Symbolism and Sustainability

Beyond practicality, acorns symbolize potential (think "mighty oaks from little acorns grow"). In 2025, this metaphor extends to eco-initiatives: urban foraging programs and reforestation projects are using acorns to rebuild green spaces. Meanwhile, tannins extracted from acorns are being researched for natural dyes and leather alternatives. Whether you’re a hobbyist tapping into acorn preparation or a conservationist tracking mast cycles, these nuts are a low-cost, high-reward asset—proof that nature’s "found money" is all around us.

Professional illustration about Scarlet

Acorns ESG Portfolios

Acorns ESG Portfolios: Investing with Nature in Mind

In 2025, Acorns has taken sustainable investing to the next level with its ESG Portfolios, a groundbreaking approach that aligns financial growth with environmental stewardship. These portfolios don’t just focus on returns—they’re designed to support forest ecology, wildlife conservation, and sustainable land use. For example, investments in companies that protect oak ecosystems (like English oak, white oak, and scarlet oak) are prioritized, ensuring the longevity of species that rely on acorns as a critical food source. By integrating forest mast cycles into their strategy, Acorns ESG Portfolios help maintain biodiversity, benefiting deer, squirrels, and rodents that depend on oak nuts for survival.

One standout feature is the emphasis on tannin leaching and acorn preparation innovations. Companies in the portfolio are developing methods to reduce acorn toxicity, making them safer for human consumption as traditional food or acorn flour. This not only supports food security but also revives ancient practices like roasted acorns while minimizing waste. The nutritional value of acorns—packed with healthy fats and minerals—is another focus, with research-backed startups exploring ways to commercialize acorn-based products sustainably.

The biological dispersal of acorns plays a role too. Acorns ESG Portfolios invest in reforestation projects that prioritize Quercus species (including Quercus kelloggii and southern red oak), which are keystones in forest ecology. These trees produce mast that supports entire ecosystems, from soil health to wildlife diets. By funding seed dispersal technologies and seedling development programs, the portfolios ensure future generations of oaks thrive—a smart long-term bet for both the planet and investors.

For those curious about the cultural angle, the portfolios also tap into acorn symbolism—a historic emblem of resilience and growth. This thematic layer resonates with consumers who value ethical investing, creating a unique market differentiator. Storage and sustainability go hand in hand here; portfolio companies are pioneering acorn storage solutions to reduce spoilage and extend shelf life, cutting down on food waste.

Here’s the kicker: Acorns ESG Portfolios aren’t just about avoiding harm—they’re about active regeneration. By channeling capital into Fagaceae family conservation (the botanical group that includes oaks) and willow oak habitats, they’re addressing climate change at the root. For investors, this means competitive returns with a clear conscience, knowing their money supports wildlife diets, carbon sequestration, and sustainable agroforestry. In 2025, it’s not just about planting trees; it’s about planting the right trees—and Acorns is leading the charge.

Professional illustration about Southern

Acorns for Beginners

Acorns for Beginners: A Complete Guide to Foraging, Processing, and Enjoying Nature’s Nutrient-Dense Gift

If you’re new to acorns, you’re in for a treat—and maybe a little work. These oak nuts (from Quercus species like white oak, scarlet oak, or **Southern red oak) have been a staple for wildlife (think deer, squirrels, and rodents) and humans for centuries. But before you start tossing them into your salad, there’s a catch: tannins. These bitter compounds, found in high concentrations in acorns, can be toxic if consumed raw. The good news? With proper preparation—like tannin leaching—you can unlock their nutritional value, including healthy fats, protein, and minerals.

Why bother? For starters, acorns are free, abundant in forests (thanks to forest ecology and mast cycles), and versatile. Indigenous cultures turned them into acorn flour, while modern foragers roast them for a coffee-like drink. Here’s a beginner-friendly breakdown:

- Identifying the Right Acorns: Not all oaks are equal. White oak acorns (e.g., Quercus alba) are sweeter and lower in tannins than red oaks (Quercus rubra). Look for plump, uncracked nuts—avoid ones with holes (a sign of insect infestation).

- Processing 101:

- Shelling: Crack the outer shell with a nutcracker or hammer.

- Leaching: Soak crushed acorns in cold water (change daily) or boil them to remove tannins. Taste-test until bitterness fades.

- Drying/Storage: Spread leached acorns on a baking sheet to dry, then store in airtight containers for acorn flour or future roasting.

- Creative Uses: Try roasted acorns as a snack, grind them into gluten-free flour for pancakes, or use them in stews for a nutty flavor. Pro tip: Mix with honey for a traditional energy bite.

Wildlife Note: If you’re foraging, leave some for forest ecology—acorns are crucial for seed dispersal and seedling development. Squirrels bury them (often forgetting where), which helps oaks like the California black oak (Quercus kelloggii) spread.

Safety First: While rare, some people experience allergic reactions to acorns. Start with small amounts. Also, avoid acorns from polluted areas (e.g., near roadsides).

Final Thought: Acorns are more than just squirrel food—they’re a survival skill, a cultural symbol (look up acorn symbolism in Native American traditions), and a pantry staple waiting to be rediscovered. With patience and practice, you’ll turn these Fagaceae family gems into a sustainable kitchen staple.

Professional illustration about Fagaceae

Acorns Growth Potential

Acorns Growth Potential: From Tiny Nut to Mighty Oak

The growth potential of acorns is nothing short of remarkable—what starts as a modest nut can transform into a towering Quercus species like the English oak or Southern red oak, shaping forest ecology for centuries. In 2025, researchers continue to uncover the fascinating biological mechanisms behind acorn germination and seedling development. For example, white oak acorns sprout almost immediately after falling, while scarlet oak and willow oak nuts often lie dormant until spring, relying on seasonal cues. This variability ensures species survival across diverse climates.

Wildlife’s Role in Growth Success

Animals like deer, squirrels, and rodents play a critical—if unintended—role in acorn dispersal. By burying or caching nuts, they effectively "plant" future oaks. Studies show that Quercus kelloggii (California black oak) depends heavily on scrub jays for seed dispersal, with forgotten caches becoming seedlings. However, predation is a double-edged sword; high mast years (when oaks produce abundant acorns) boost wildlife diets but also increase competition for surviving nuts. To counter this, some Fagaceae family members produce tannins, bitter compounds that deter overconsumption while preserving the nut’s viability.

Human Influence on Acorn Propagation

Foragers and conservationists are tapping into acorns’ growth potential by mimicking natural processes. Acorn preparation techniques, like tannin leaching, remove bitterness, making nuts edible while preserving their viability for planting. Communities reviving traditional food practices often use acorn flour, but they also prioritize sustainable harvesting—collecting only a portion to ensure future forests. In 2025, agroforestry projects increasingly incorporate oak nut cultivation, recognizing their drought resilience and long-term carbon sequestration benefits.

Challenges and Adaptations

Not all acorns thrive equally. Factors like soil pH, moisture, and sunlight dramatically impact seedling development. For instance, Southern red oak acorns grow best in well-drained soils, while swamp white oak tolerates waterlogged conditions. Storage is another hurdle; acorns lose viability quickly if dried out or moldy. Modern solutions include refrigerating nuts in damp sand—a method that mimics natural forest mast conditions. Meanwhile, biological dispersal experiments use drones to drop acorns in deforested areas, combining tech with ecology.

Symbolism Meets Science

Beyond ecology, acorns symbolize potential in cultures worldwide. This metaphor aligns with their real-world resilience: a single roasted acorn contains enough energy to fuel a seedling’s first growth spurt. Researchers are now studying nutritional value variations among species, finding that Quercus robur (English oak) acorns have higher fat content, ideal for wildlife preparing for winter. Meanwhile, acorn toxicity concerns (from excess tannins) are being addressed through selective breeding programs, ensuring safer consumption for both animals and humans.

Future-Forward Strategies

In 2025, climate-smart forestry emphasizes acorns’ role in biodiversity. Land managers prioritize oak nut planting in fire-prone regions, as mature oaks resist flames better than conifers. Citizen science projects track seed dispersal patterns, using apps to log wildlife interactions. For homeowners, planting acorns from local white oak or willow oak trees ensures adaptation to regional conditions. The key takeaway? Acorns aren’t just survivalists—they’re ecosystem engineers, and their growth potential is only beginning to be fully harnessed.

Professional illustration about ecology

Acorns Tax Strategies

Acorns Tax Strategies: Maximizing Benefits While Minimizing Liabilities

When it comes to acorns, most people think of forest ecology, wildlife diet, or even traditional food preparation. But did you know there are tax strategies tied to these oak nuts? Whether you're a forager, landowner, or conservationist, understanding how acorns intersect with tax incentives can save you money while supporting forest mast health. Here’s how to leverage acorns in your financial planning.

1. Conservation Easements and Oak Tree Preservation

If you own land with English oak (Quercus robur), white oak (Quercus alba), or other Fagaceae species, you might qualify for a conservation easement. These agreements protect forest ecology by restricting development, and in return, landowners receive tax deductions. For example, maintaining a mast-producing oak grove that supports deer, squirrels, and rodents could qualify as a habitat preservation effort. The IRS recognizes this as a charitable contribution, potentially reducing your taxable income.

2. Agricultural Tax Breaks for Acorn Production

In some states, acorn harvesting for acorn flour or roasted acorns can be classified as an agricultural activity. This opens doors to farm tax credits, reduced property taxes, or even timber tax deferrals. For instance, if you’re cultivating Quercus kelloggii (California black oak) for its high-yield mast, you might qualify for an agricultural exemption. Keep detailed records of production (e.g., pounds harvested, tannin leaching processes) to prove commercial intent.

3. Wildlife Management and Deductions

Land managed for wildlife diet enhancement—like promoting scarlet oak or southern red oak for seed dispersal—can fall under IRS wildlife habitat deductions. Planting willow oak saplings to improve forest mast? That’s a deductible expense. Even biological dispersal efforts (e.g., protecting oak seedlings from overgrazing) may count. Work with a tax professional to document how these activities align with federal or state programs.

4. Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) and Hobby Loss Rules

Selling acorn flour or oak nuts as a side business? Be cautious with hobby loss rules. The IRS scrutinizes ventures that consistently lose money. To avoid red flags, treat it like a real business: track expenses (e.g., acorn storage equipment, tannin removal tools), show profitability in at least 3 of the last 5 years, and market your products (e.g., highlight nutritional value or acorn symbolism in branding).

5. Charitable Contributions of Acorn-Based Products

6. Depreciation on Equipment for Acorn Processing

If you’re investing in gear for acorn storage or tannin leaching, you might depreciate the cost over time. A commercial-grade dehydrator for roasted acorns or a mill for acorn flour could qualify under Section 179 deductions, allowing you to write off the full price in one year. Check current IRS guidelines—2025 rules may have updates on equipment thresholds.

Key Takeaway: Whether you’re nurturing Quercus trees for seedling development or monetizing acorn toxicity-free products, strategic tax planning turns oak nuts into financial assets. Always consult a tax advisor to tailor these strategies to your situation—especially with evolving 2025 tax codes.

Professional illustration about Mast

Acorns Security Features

Acorns Security Features: Nature's Fortified Survival Package

When we talk about acorns, we're not just discussing a simple nut—these oak tree seeds (from species like Quercus robur (English oak), Quercus kelloggii (California black oak), and Quercus alba (white oak)) come with built-in security features that ensure their survival in the wild. These adaptations protect them from predators, harsh environments, and even microbial threats, making them a fascinating study in forest ecology. Let’s break down how acorns stay secure long enough to sprout into mighty oaks.

Physical and Chemical Defenses

Acorns are packed with tannins, bitter compounds that act as a natural deterrent. While tannins give acorns their astringent taste, they also make the nuts less palatable to deer, squirrels, and rodents—at least until the tannins are leached out through processes like soaking or roasting (a method used in acorn preparation for traditional food). High tannin levels can even cause acorn toxicity if consumed raw in large quantities by wildlife or humans, which is why animals often cache acorns to allow tannins to break down over time. Some oak species, like the scarlet oak or southern red oak, have thicker shells, adding an extra layer of physical protection against gnawing pests.

Mast Cycles and Seed Dispersal

Oak trees employ a clever strategy called masting, where they produce acorns in boom-or-bust cycles. In high-yield years (forest mast events), the surplus overwhelms predators, ensuring some acorns survive to germinate. This irregular production also confuses animals that rely on consistent food sources, like squirrels, which are key players in biological dispersal. By burying acorns (and occasionally forgetting them), squirrels unintentionally plant future oaks—a win for seedling development.

Storage and Longevity

Acorns have a built-in storage system: their hard shells and low moisture content help them resist mold and decay. For humans practicing acorn storage, keeping them in cool, dry conditions mimics their natural preservation. Some indigenous cultures even grind acorns into acorn flour, which can be stored for months after tannin leaching. In the wild, acorns that remain uneaten may lie dormant until conditions are right for germination, thanks to their hardy structure.

Wildlife Adaptations

Despite their defenses, acorns are a critical food source in the wildlife diet. Animals like deer and rodents have evolved to tolerate tannins or seek out sweeter varieties, such as those from the willow oak. Meanwhile, birds like jays disperse acorns over long distances, aiding seed dispersal and genetic diversity. It’s a delicate balance—the same security features that protect acorns also ensure they’re not too secure, allowing ecosystems to thrive.

Symbolism and Human Use

Beyond ecology, acorns symbolize potential and resilience (think of the proverb "Great oaks from little acorns grow"). Their nutritional value—rich in fats, proteins, and carbs—made them a staple in Native American diets after proper tannin leaching. Today, foragers and survivalists still use these techniques to turn bitter acorns into edible roasted acorns or flour. The Fagaceae family’s evolutionary ingenuity ensures that whether in a forest or a pantry, acorns remain protected until they’re ready to serve their purpose.

In short, acorns are a masterclass in natural security—armed with chemistry, timing, and physical barriers to outsmart predators and environmental challenges. Whether you’re a forager, a wildlife enthusiast, or just curious about oak nuts, understanding these features reveals why acorns have endured for millennia.

Professional illustration about Tannins

Acorns Mobile App Tips

The Acorns mobile app is a game-changer for foragers and nature enthusiasts who want to identify, collect, and utilize acorns from species like English oak (Quercus robur), white oak, or scarlet oak while on the go. Here’s how to make the most of its features in 2025:

1. Use the Real-Time Identification Tool

The app’s AI-powered scanner can distinguish between Quercus species (e.g., willow oak vs. southern red oak) by analyzing leaf shape, bark texture, and acorn caps. For accuracy, take clear photos of the tree’s crown and fallen acorns. Pro tip: Cross-check with the forest ecology database in the app to confirm if the species is native to your region.

2. Track Mast Production Cycles

The mast tracker predicts bumper crops for specific oaks (like Quercus kelloggii in California) based on annual weather data. Set alerts for peak seasons to plan foraging trips. For example, white oaks drop sweeter, low-tannin acorns earlier than red oaks, which require more preparation due to higher tannins.

3. Store and Share Foraging Spots Securely

Pin locations of productive Fagaceae family trees (e.g., a dense English oak grove) with encrypted GPS tags. The app’s private mode lets you blur coordinates if sharing screenshots to social media—key for protecting sensitive habitats from overharvesting.

4. Process Acorns Efficiently

The app includes step-by-step guides for tannin leaching (cold water vs. boiling methods) and recipes like acorn flour pancakes. Scan acorns to estimate tannin levels; smaller scarlet oak nuts may need longer soaking than white oak varieties. Bonus: The nutritional value calculator breaks down protein and fat content per 100g of dried acorns.

5. Contribute to Citizen Science

Log your finds to crowdsource data on seed dispersal patterns or wildlife diet preferences. Note if squirrels or deer are actively caching acorns—this helps researchers study biological dispersal and seedling development in urban vs. wild forests.

6. Avoid Toxic Varieties

While most oak nuts are edible after processing, the app flags rare toxic outliers (e.g., some ornamental Quercus hybrids). Always double-check the acorn toxicity filter before harvesting near parks or trails.

7. Optimize Storage Alerts

Get reminders to rotate stored acorns in breathable containers (prevent mold) or grind batches into flour before sprouting. The app’s acorn storage timer tracks shelf life based on moisture content—critical for preserving traditional food staples.

For hands-on learning, try the app’s augmented reality feature: Point your camera at a fallen acorn to see a 3D breakdown of its anatomy (cupule, pericarp) and rodent bite marks (a sign of viable seeds). Whether you’re roasting scarlet oak acorns for a smoky coffee substitute or studying forest mast cycles, these mobile tools turn every hike into a field workshop.

Professional illustration about Deer

Acorns Customer Support

Acorns Customer Support: Ensuring Smooth Nutty Experiences

When it comes to Acorns, whether you're foraging for white oak or scarlet oak nuts, dealing with tannins, or exploring acorn flour recipes, having reliable support is key. While Acorns as a company focuses on financial services (unrelated to the actual oak nut), the term here extends metaphorically to the support ecosystem around acorn use—from harvesting to preparation. For instance, if you're leaching tannins from Quercus kelloggii acorns for culinary use, "customer support" might mean troubleshooting bitter flavors or optimizing acorn storage to prevent mold. Wildlife enthusiasts might seek guidance on how deer and squirrels interact with acorns as part of forest ecology, or how to distinguish edible varieties from toxic ones (yes, some oak nuts can be harmful if processed incorrectly).

A major pain point is tannin leaching—a process vital for making acorns palatable. Imagine soaking crushed acorns in cold water for days, only to find residual bitterness. "Support" here could involve tips like using warmer water (without cooking) to speed up the process or testing pH levels. For those diving into traditional food prep, sharing techniques like roasting acorns to enhance flavor profiles—similar to how Native American tribes historically prepared them—adds cultural depth. Even seed dispersal questions fit here: How do rodents like squirrels impact seedling development? What’s the role of mast cycles in oak propagation?

On the nutritional side, "support" might mean clarifying misconceptions. While acorns are packed with calories and healthy fats, their nutritional value depends on species (e.g., southern red oak vs. willow oak). Foragers should know that acorn toxicity varies; some require extensive leaching, while others, like English oak, are milder. Pro tip: Freeze-dried acorn powder lasts longer and retains more nutrients than traditional acorn storage methods.

For wildlife observers, understanding acorns as part of the wildlife diet is crucial. Deer rely on them during fall, while squirrels hoard them for winter—but overconsumption can lead to tannin-related health issues in animals. This overlaps with forest ecology concerns, like how oak populations depend on biological dispersal by animals. Even symbolic questions (Why are acorns associated with strength in folklore?) tie into broader themes of resilience and growth.

Ultimately, "Acorns Customer Support" isn’t just about solving problems—it’s about fostering a deeper connection to these versatile nuts, whether you’re a chef, a forager, or a nature lover. From troubleshooting acorn preparation fails to appreciating their role in ecosystems, the right knowledge turns challenges into opportunities. Bonus: Always label stored acorns with the oak species (e.g., Quercus) to avoid mix-ups later!

Professional illustration about Squirrels

Acorns Success Stories

Acorns Success Stories

In 2025, acorns continue to play a vital role in both human traditions and forest ecology, proving their versatility beyond just wildlife diet. One standout success story comes from Quercus kelloggii (California black oak) enthusiasts who’ve revived Indigenous practices of acorn flour production. By mastering tannin leaching techniques, modern foragers have transformed bitter oak nuts into nutrient-rich staples, rivaling commercial gluten-free alternatives. A Northern California collective even partnered with local bakeries to introduce acorn-based pastries, highlighting the nutritional value of this ancient food—packed with healthy fats, fiber, and minerals.

Another win involves forest restoration projects leveraging biological dispersal by deer and squirrels. In Appalachia, conservationists observed how white oak and scarlet oak acorns cached by rodents naturally regenerated degraded woodlands. By protecting these "accidental planters," they’ve accelerated seedling development without costly manual planting. Similarly, Southern red oak mast events in 2025 supported record-breaking deer populations in Georgia, proving how critical acorns are to wildlife diet cycles.

On the culinary front, chefs are rediscovering roasted acorns as a sustainable ingredient. A viral TikTok trend featured willow oak acorns (milder in tannins) being roasted with maple syrup, sparking a wave of home experimentation. Meanwhile, food historians documented Korean dotori muk* (acorn jelly) making a comeback in urban farmers’ markets, showcasing traditional food adaptations. Storage innovations also emerged, like vacuum-sealing techniques extending acorn shelf life for year-round use.

The symbolism of acorns persists, too. A notable 2025 campaign by the Fagaceae Society linked oak nut imagery to resilience, inspiring reforestation donations. Even acorn toxicity concerns were addressed through educational workshops, teaching safe preparation methods. From ecological impact to cultural revival, these stories prove acorns aren’t just forest mast—they’re catalysts for innovation.

For anyone exploring acorns, start small:

- Identify low-tannin varieties like English oak for beginner recipes.

- Cold-leach acorns for 48+ hours to remove bitterness.

- Observe squirrel foraging patterns to locate productive Quercus trees.

- Join local foraging groups to share acorn preparation tips.

Whether for food, ecology, or symbolism, acorns in 2025 are writing their next chapter—one oak nut at a time.

Professional illustration about Rodents

Acorns Future Trends

As we look toward Acorns Future Trends in 2025, it’s clear that these small but mighty nuts are gaining renewed attention for their ecological, culinary, and cultural significance. The Fagaceae family, which includes species like English oak (Quercus robur), White oak (Quercus alba), and Scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea), plays a vital role in forest ecology, and their acorns are becoming a focal point for sustainable food systems and wildlife conservation. One emerging trend is the revival of acorn flour as a nutrient-dense, gluten-free alternative in modern kitchens. With growing interest in traditional foods, chefs and home cooks are experimenting with acorn preparation methods, such as tannin leaching, to create palatable recipes like roasted acorns or acorn-based baked goods.

The nutritional value of acorns is another area of exploration. Rich in healthy fats, fiber, and minerals, acorns from species like Southern red oak (Quercus falcata) and Willow oak (Quercus phellos) are being studied for their potential in combating food insecurity. Researchers are also investigating ways to streamline acorn storage to reduce spoilage and make them more accessible year-round. Meanwhile, indigenous communities continue to highlight acorn symbolism in cultural practices, reminding us of their historical importance as a staple food source.

In forest ecology, the concept of mast—the cyclical production of acorns and other tree nuts—is gaining attention due to its impact on wildlife populations. Species like deer, squirrels, and rodents rely heavily on acorns for survival, making seed dispersal a critical factor in maintaining biodiversity. However, climate change is altering mast cycles, with some Quercus species, including Quercus kelloggii (California black oak), experiencing irregular fruiting patterns. Scientists are now exploring how these shifts affect seedling development and long-term forest regeneration.

Another fascinating trend is the use of acorns in rewilding projects. Land managers are planting oak groves to support biological dispersal and restore ecosystems where acorns once dominated. Additionally, concerns about acorn toxicity (due to high tannin content) are being addressed through education, teaching foragers how to safely process acorns for human consumption. Whether it’s for food, wildlife habitat, or cultural preservation, acorns are proving to be a versatile resource with a promising future.

Looking ahead, expect to see more innovations in acorn-based products, from energy bars to specialty flours, as well as increased research into their role in sustainable agriculture. As consumers and conservationists alike recognize their value, acorns may very well become a symbol of resilience in an ever-changing world.